GUEST ARTICLE - Creativity in the early years or ‘how NOT to cheat children….’*

By Simon Taylor MA, FRSA

In this month’s guest article, "Creativity in the Early Years or ‘How NOT to Cheat Children…’" by Simon Taylor MA, FRSA, he explores the meaning of creativity in early childhood education and how to genuinely foster it.

Understanding Creativity - Exploring different definitions of creativity and why it is essential for children’s development and well-being.

Debunking Myths - Challenging misconceptions that creativity is only about the arts, is always fun, or does not require skill or knowledge.

Fostering Creativity in Practice - Emphasising the importance of focusing on the process over the product, using open-ended materials like ‘loose parts’, and supporting child-led exploration.

Creating Supportive Environments - Encouraging educators to create settings that nurture children's natural curiosity, imagination, and creative thinking, even if it means stepping back and allowing children to explore in their own ways.

Creativity in the early years or ‘how NOT to cheat children….’*

By Simon Taylor MA, FRSA

‘Creativity’ is such a commonplace term and taken-for-granted idea that there is a general feeling that surely, we must all agree on what it is, what it looks like and that it must always inherently be ‘a good thing’ in the context of children’s learning…

However, how many of us have ever stopped to think; what do we actually mean by ‘creativity’? how might we define it? when do we know it is really happening? and why are some well-intentioned ‘creative activities’ sometimes problematic and anything but creative?

In my book I address these and other questions by exploring definitions of creativity, discussing why it is so important for children’s wellbeing and development and showing how we might authentically foster it in the early years.

Firstly, how do we define creativity? This can be problematic and no doubt we all have slightly different definitions that are personal to us. Some commentators have found it helpful instead to define what creativity looks like in practice. It is generally agreed that the key characteristics of creativity are:

· Imagining

· Deep engagement (or ‘flow’)

· Enquiring

· Exploring ideas and possibilities

· Tolerating ambiguity

· Risk-taking

· Self-expression

· Playfulness

· Making connections

· Composing

· Curating

· Expressing

· Responding to an aesthetic (a sensory) experience

Whilst there are many different perspectives in the literature, I prefer to take the democratic view that ‘everyone is creative’ and that creativity manifests itself as curiosity, imagination and divergent thinking in young children- the ability to think of multiple alternatives to any given question or scenario (Robinson, 2016), something that must be encouraged. The late Ken Robinson, educationalist and inspirational speaker, was a passionate advocate for children’s innate creative ability and considered it part of a life-long process of ‘finding your element’ or natural talent (2010). Early Years expert Tina Bruce linked this to the idea of ‘agency’, stating that, ‘creativity is part of the process through which children begin to find out they have something unique to ‘say’, in words or dance, music, or hatching out their theory’ (Bruce, 2011, p.12).

Some writers and commentators make the case that children are fundamentally ‘born creative’ (Tims, 2010) and that every child can be considered to have creative potential and to be capable of creative expression. English author and former Children’s Laureate, Michael Rosen, is passionate about the potential of every child and the importance of supporting creativity to enable real learning. He is also very clear about the complexity of this process,

…learning is complex. It isn’t a piece of one-dimensional travel along one axis. We make advances and retreats. The retreats may well be in the long run advances; some advances may be cul-de-sacs. These free-flowing processes can be inhibited in many ways, one of which comes from giving people a fear of failure. If you are afraid to travel about in the multidimensions of learning, you will be prevented from getting to the next step. Michael Rosen (2010, p.12)

What is the fundamental role of creativity in these ‘multi-dimensions of learning’? Rosen firmly believes it is the ability to be ‘open to receiving ideas, processes, sensations and feelings’ (2010, p.12) and then being allowed to respond by being given a sense that there are ‘many ways of getting things right’, rather than a simple binary of ‘right or wrong’ (see Fig.1 ‘Expressive mark-making). Also important is having time to reflect on any ‘product’ or simply the process itself, and perhaps doing so in co-operation with others. In this way we make personal meaning and true learning can take place.

Early years practitioners often make the mistake of prescribing this end product in carefully planned ‘creative activities’ (e.g. decorating the classic Christmas card in a production line - so beloved of parents!), rather than focussing on the process and paying attention to the child’s interests; what are they really exploring? what fascinates them about the activity? how are they expressing themselves? how deeply are they engaged in the task? what are they trying to say? In this way we can truly develop a ‘pedagogy of listening’ in the words of Loris Malaguzzi, educational psychologist and pioneer of creative, child-led curricula known as the ‘Reggio Approach’ (Rinaldi, 2021). It also ensures that children do not develop that ‘fear of failure’ that Rosen refers to, which can take hold quickly and is so often the hallmark of unhappy school experiences when they make the transition to Key Stage 1 and beyond.

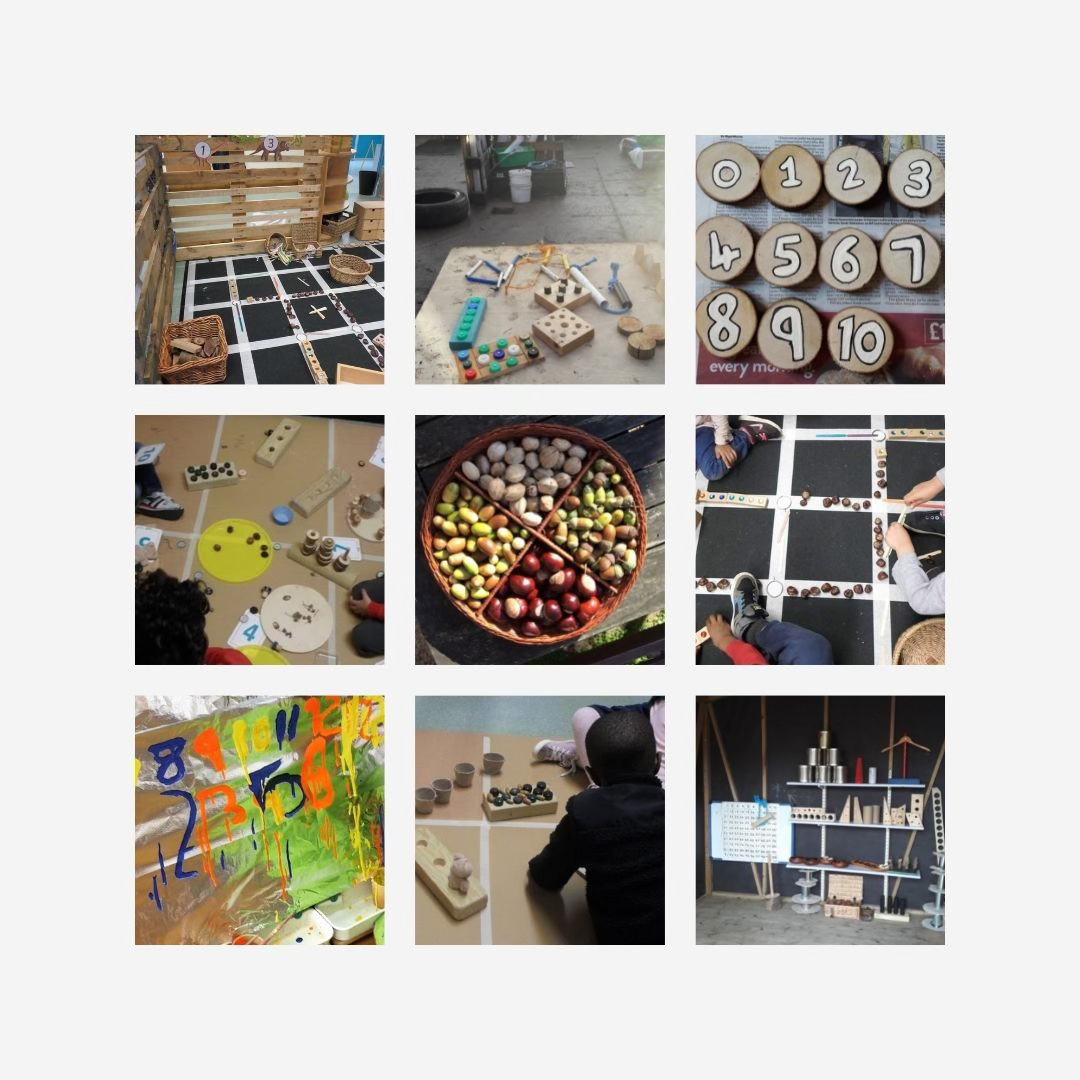

It is important in this context to acknowledge the power of free play, choice and the value of discovery. Low-cost objects or recycled items (‘loose parts’) invite children to use them in multiple ways (see Fig.2 Loose parts). There may be many variables or uses (‘affordances’) in each object and this can encourage active learning that is developmentally inclusive and open-ended.

Research has also identified some commonly held myths about developing young children’s creativity; that it is limited to arts subjects, that the creative process is ‘fun’ and should not be taken too seriously (in reality it requires concentration, persistence and determination and may be a frustrating and difficult process), that free play and unstructured activities are sufficient creative experience (this can become routine and repetitive, children need stimulation and creative problems to solve), that it does not require knowledge or skill (these are fundamental to creativity, people cannot fully express their creativity without the necessary skills or understanding of the area) and that children find it easy to transfer learning from one domain to another (children can struggle with context-specific knowledge so adults should help children to make connections) (Sharp, 2004).

Indeed, viewing creativity as solely or mainly the domain of ‘creative’ subjects such as art, drama or music is a common misconception because it can lead to a denial of the role of creativity in other areas, such as science and mathematics (see Fig. 3 Natural maths: Creative and play-based approaches to learning mathematics). Creativity is not subject-specific and if we see it as ‘curiosity’, ‘imagination’ and a way of approaching problem-solving then it can be utilised in different domains. It does not take place in a vacuum and the way in which children express this curiosity through creativity will be different in different curriculum areas (Sharp, 2004).

In conclusion, authentic opportunities for creativity in early years settings are ones that encourage imagination, support children’s natural curiosity and pay attention to their interests, prioritising the process rather than the end product. It can be challenging for early years practitioners to relinquish ‘control’, but if we are serious about supporting children’s learning and development then we need to design environments and activities that support the key characteristics of creativity.

*Title inspired by British Architect Simon Nicholson who published his seminal article in the early 1970s on creativity and the nature of children’s play: ‘How NOT to cheat children: The Theory of Loose Parts’ (1971)

Simon Taylor MA, FRSA

Simon is a Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Education, University of Worcester. Prior to this he worked in the arts and cultural sector as Head of Learning for Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery (2011-2015) and Education and Community Outreach Manager for an arts development agency based in Hampshire (2004-2011). Originally a graduate of the University of Brighton, Simon worked as a professional artist in the South East, teaching in a range of settings including Special schools, Children’s Centres, Prison Education and FE colleges. He has worked with a diverse range of learners including vulnerable adults, young people at risk from exclusion, children with special needs, prisoners and young offenders.

Simon is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (HEA) and a Fellow of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (FRSA).

Contact email: simon.taylor@worc.ac.uk

Linked In: https://www.linkedin.com/in/simon-taylor-frsa-71607910/

Staff Profile: https://www.worcester.ac.uk/discover/Simon-Taylor.html

References

Bower, L. (2005) Everyday Learning About Imagination. Everyday Learning Series. Volume 3 (4), p.3

Bruce, T. (2011) (2nd ed.) Cultivating Creativity: for babies, toddlers and children. Oxford: Hodder Education

Rinaldi, C. (2021) (2nd ed.) In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, Researching and Learning. Abingdon: Routledge

Robinson, K. (2010) The Element: How finding your passion changes everything. London: Penguin

Robinson, K. (2016) Creative Schools. London: Penguin Books

Rosen, M. (2010) Forward In Tims, C. (ed.) Born Creative. London, DEMOS

Sharp, C. (2004) Developing Young children’s Creativity: What can we learn from research? NFER. Available at: https://futurelab.org.uk/developing-young-childrens-creativity-what-can-we-learn-from-research/

Tims, C. (ed.) (2010) Born Creative. London, DEMOS

It’s great to read about how creativity can look in practice. Children are so creative and can think of ways of expressing themselves that we as adults haven’t even thought of.

Absolutely! Creativity is about being curious and arts and crafts are just a way, in my opinion, of channeling that inspiration. As an adult I like to make sculptures with wool using the needle felting technique and it is a very slow and repetitive process but what I absolutely love is to create. Even I struggle to believe that I made that cute whatever it us out of stabbing wool for a good bunch of hours. I am in the flow and I love to channel my energy that way.