Teaching Your Children to Count is Stopping Them Developing Mathematical Understanding

Why Counting Alone Stops Real Understanding - by Karen Wilding

Hey PLAYlisters,

This month’s guest article comes from the brilliant Karen Wilding. Karen is the founder and director of EYMaths and is on a misson to improve the understanding of effective maths in the early years.

This article explores the concept of subitising and its foundational role in maths and more!

If you enjoy the article, make sure to check out the conversation Karen and I had all about early maths, introducing counting and why it might be time for a new approach. The interview is available for free this month to paid subscribers, and you can find it here:

Why Counting Alone Stops Real Understanding

By Karen Wilding

Say the word ‘Maths’ and the first thing that comes to mind for most people is ‘Numbers’.

Ask what ‘learning about numbers’ means to most this, we are most like to hear, particularly when thinking about our youngest children, ‘learning to count’.

In education, developing a child’s deep understanding of ‘Numbers’ is known as ‘Number Sense and it’s crucial to enabling every child to feel and work confidently in Mathematics for life.

The Problem (and one of the key reasons so many children and adults dislike and struggle with Maths)

What if I said that the approach we’re all most familiar with; teaching children to count to find out ‘How many?’, is actually STOPPING them developing this vital ‘Number Sense’?

Let’s explore this more and you can decide for yourself.

The ‘counting system’, using number names and symbols in a set order, is a human invention.

We’re all aware of previous systems humans used in the past, such as Roman Numerals, and can see that the symbols we use today in what’s known as the ‘Hindu/Arabic’ counting system, are very different.

Humans have always had a need to compare amounts and understand ‘Which is more?’ For example, when hunting for food I might select one particular way over another if I see more of what I’d like to eat in one direction but, likewise, when comparing two different sized groups of ‘scary’ animals (the ones who might like to have me for dinner), I would head towards the smaller group where fewer means I’m increasing my chances of survival!

Other problems our ancestors would have frequently needed to solve include wondering ‘Is there enough for everyone to have some?’ when dividing up precious food or resources.

Consider both scenario I’ve described above. Can you see that the humans solving these problems did not need a number system to do so? The skill our ancestors used (and we still use today) is concerned with judging and comparing whole amounts (in the first example) and matching amounts 1:1 or determining the quantity something must be split into equally and sharing out. Because we can name these amounts, we sometimes struggle to see that if we saw what we would called ‘4’ people in front of us and we had a flat loaf, for example, we could ‘see’ that we needed to match equal parts of the bread to the people. Try it out for yourself and see.

The best evidence of this skill in action today is with babies and toddlers. Babies offered two different amounts of the same favourite food, will typically choose the larger amount. Their brain is designed to keep them alive and knows that being able to select the amount that will sustain them for longer. The baby doesn’t consciously know this but doesn’t need to. It’s an automatic, built in response.

Likewise, there are a number of videos ‘doing the rounds’ on social media in recent times showing twins and their mother. The mother gives one twin a plate with 4 biscuits on it and the other twin an empty plate. The first twin looks at the two plates and then picks up two biscuits and moves them to their siblings’ plate. Both then look at their plates and happily begin to eat the biscuits.

We know in both of these cases that the children are not counting. They haven’t learned this (highly complex) skill yet.

So, what are they doing and will teaching them to count to find out ‘How many?’ actually prevent this natural ‘number sense’ growing and becoming connected to our human-made ‘number system’?

This skill the babies and toddlers are using here is known as ‘subitising’ and it’s the ability to ‘know how many’ without needing to count. Other animals and even plants have been shown to have this skill too (how else does a mother duck know one of her ducklings is missing?)

‘Subitising’ (coming from the Latin ‘subito’ meaning ‘ to arrive suddenly’) has now found its way into many of the world’s Maths’ curricula, schemes and approaches but it’s often portrayed in an over simplified way and its role in building a child’s ability to add, subtract, multiply and divide (throughout their lives) completely misunderstood and overlooked.

Development of Subitising in Its Earliest Stages (Simplified Overview)

Consider the typical age of a children you’ve observed doing this

· Noticing and comparing greater and lesser amounts and making a choice

· Noticing when something is ‘not there yet’ e.g. a missing cup for someone, a missing part in a puzzle or sock for a foot

· Matching amounts so there’s ‘enough’ e.g. making sure everyone has a cup each

· Saying ‘more’ and then moving to ‘one more’ and adding to a set

· When looking at a book together says things like ’Look, 3 elephants!’ and ‘No more elephants; elephants gone away’

· Holds up fingers in response to a question that requires communication of more or a desired amount e.g. holds up 2 fingers (may not say ‘2’ or may say another number names at this stage, number names are merely words), holds up 1 finger and then re-considers and puts up another, holds up all fingers and may use yours too to communicate ‘lots and lots’!

· Usually with adult modelling and encouraging curiosity and language, begins to consistently notice and label amounts of 1, 2 and 3 things in everyday interactions, such as making a snack (I’ve got 3 strawberries and you have only got 2’ ) or exploring nature ‘There’s 3 flowers’.

In examples, where the child is beginning to notice and label groups of everyday objects and images in books, notice that they are not counting the items using ‘1, 2, 3 etc.’ Instead, they are viewing the group as a whole and labelling it as such. Being able to see an amount is equal, more or less than another amount and then later attach a number name to it (a name that changes in every language – evidence that this is merely a way of representing a number and is not the number itself) is known as ‘perceptual subitising’ and forms an essential foundation on which their ability to add, subtract, multiply and divide is built.

There’s a great deal more to share to answer all the questions that will begin bubbling up in our minds reading what we have so far ‘But where does counting fit in then? Are you suggesting we don’t teach them to count at all? What about numbers bigger than 3?’and more. These are the questions I hear whenever someone has the opportunity to stop and think about how we are teaching our children ‘Number Sense’ and what is leading to the continued widespread dislike and failure in Maths for a significant proportion of the population.

In this introduction to building ‘Number Sense’ let’s go just one stage further.

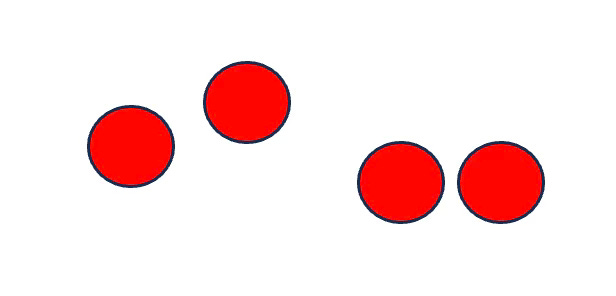

Look at the image below.

What do you see? How do you see it?

If I said I can see ‘two and two’ could you ‘circle ‘your finger around where I might be looking? Is there just one way of seeing this or could you move your finger around different groups of two within the whole?

What if you looked at this amount in a different way? What else do you see?

If I said I can see ‘A one and a one and two’ could you predict and ‘circle’ with your finger where I might be looking?

What about ‘A one and a one and one and one?’

What about ‘A three and a one?’

Here, we’re using our ‘perceptual subitising’ skills to see ‘parts within the whole’ (or ‘part/whole’ as it’s known in Maths teaching).

Understanding that this quantity (that we know as ‘four’) is made up of four ‘1s’, two ‘2s’, ‘one 1 and one 3’ and ‘one 2 and two 1s’ means we are developing the tools to solve 2 + 2 = ?. If four has two 2s in it then 2+ 2 must equal 4. If 1 had four things and I gave away one to you I’d have three remaining. This written using abstract symbols in a calculation is 4 - 3 =3.

What about four divided into two equal groups? Can you see that this would give us two in each group? 4 ¸ 2 = 2

What about the ‘counting in 2’s’ (the 2 times table)? Can you see that 2 groups of 2 are equal to 4? 2 x 2 = 4

But How Does This Compare to Counting? Why say ‘don’t count’?

Let’s count these spots instead?

Does that mean that there is only one ‘2’ in 4?

And how will this help me if I’m asked 4 – 2 = ?

If I take away the ‘2’ perhaps I’m left with the 1, 3 and the 4?

Why are we giving each counter a different name but then expecting a child to call them all by the last number name they said?

We ask ‘How many? Child counts ‘1, 2, 3, 4’ We ask ‘How many?’ again and expect then to label the ‘1’ as a ‘4’ , the ‘2’ as a ‘4 ‘and the 3 as a ‘4’ (only the ‘4’ gets to keep it’s label). What a strange rule.

As you’ll no doubt suspect, there’s a great deal more to dig into and share here to reveal the journey that WILL give every child the ability to understand and use numbers flexibly and with ease, or what we call having ‘Number Sense’.

The good news is that counting DOES still play a vital role (but just not in the way you’d expect or have been using it all your life…)

To continue this journey and find out more about how subitising and counting work together to build Essential Number Sense’ visit EY Maths here .

You can also find Karen here

Facebook: EYMaths 3-7 https://www.facebook.com/groups/609926063189767

Instagram: @eymaths_

Karen Wilding is the founder and director of EYMaths, an online training company supporting educators of 3–5-year-olds in delivering meaningful and joyful mathematical learning. Her journey began with a deep fear of maths, shaped by early struggles and repeated failures, leading her to believe she lacked a "Maths gene."

Twelve years into her teaching career, Karen faced her fears when asked to teach older children. A transformative training session shifted her mindset, helping her see that the problem was how she had been taught—not her ability. This revelation sparked her passion for making maths accessible and meaningful.

Karen became a local authority maths consultant, eventually launching her own business in 2009. After the pandemic forced her to rethink her career, she founded EYMaths. Today, Karen empowers educators worldwide, ensuring children experience maths as a positive, engaging foundation for understanding the world.

Love Karen’s work, it changed the way I teach and view maths!

I discovered Karen Wilding and eymaths.co.uk during the pandemic, her thought provoking training completely transformed my practise as an early year practitioner and not just for maths but also made me rethink my pedagogy throughout the curriculum and how children learn, amazing!