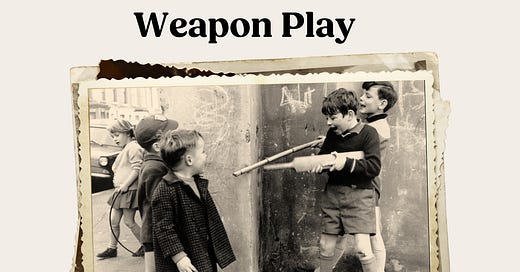

Weapon Play in the Early Years by Dr. Alistair Bryce-Clegg

An Article Exploring the Research Behind Weapon Play in Early Years.

Weapon play is a bit like the elephant in your early years classroom—impossible to ignore, yet often difficult to discuss!

Whether it’s superheroes battling imaginary villains, pirates wielding cardboard cutlasses, or knights defending a castle, children are naturally drawn to themes of power, protection, and conflict in their play. And, research tells us that banning it doesn’t work.

Instead, what if we embraced weapon play as a valuable developmental tool? What if, rather than shutting it down, we used it to support emotional regulation, social negotiation, and creative thinking? The reality is that weapon play isn’t about aggression—it’s about storytelling, problem-solving, and making sense of the world. However, we must help children distinguish between power and violence. Power is about strength, leadership, and protection, whereas violence is about harm and control. If we focus on guiding their play rather than stopping it, we can help them explore power in positive ways rather than reinforcing negative behaviours.

Why Are Children Drawn to Weapon Play?

Children don’t just engage in weapon play on a whim. It’s deeply rooted in their development. From an early age, children explore power, justice, and conflict through role play. They want to test out ideas, push boundaries, and step into the shoes of the heroes and protectors they see in books, films, and real life.

This kind of play helps them to:

Make sense of emotions – Children experience strong feelings like fear, excitement, and anger. Weapon play allows them to explore these emotions safely.

Understand social dynamics – Through role play, children explore concepts of fairness, rules, and leadership.

Develop problem-solving skills – Weapon play often involves strategy, decision-making, and negotiation with peers.

Use their imaginations – It’s not really about the ‘weapons’—it’s about the story. Whether it’s a superhero mission or a battle to save a kingdom, these narratives build creativity.

However, it is crucial that we as practitioners help children explore power without encouraging violence. The key difference is that power involves leadership, protection, and fairness, while violence involves control, harm, and fear. Through well-managed play, we can ensure children engage in power dynamics positively rather than reinforcing aggression.

The Big Question: Does Weapon Play Encourage Aggression?

This is the concern that makes many settings ban weapon play outright. But the research tells a different story.

Pretend battles, superheroes, and ‘goodies vs. baddies’ play do not make children more violent. In fact, banning weapon play can lead to frustration and secrecy—children will find a way to play it, whether we allow it or not.

What’s more, structured weapon play actually helps children learn self-control. It gives them a chance to test boundaries in a safe, socially accepted way. If we model positive play, help children understand limits, and step in when things escalate, we can use weapon play to reinforce self-regulation rather than suppress it.

Again, the focus must be on helping children distinguish between power and violence. If we see play becoming aggressive, we can step in and ask questions like:

‘What’s the mission of your superhero? Are they helping or hurting people?’

‘Can your knight protect the castle without fighting? I bet you have got some brilliant ideas!’

‘Is there another way to solve this problem besides a battle?’

Encouraging children to think critically about power and being powerful. This helps them learn that real strength isn’t about hurting others—it’s about making good choices.

What About Children Who Experience Real Violence?

For some children, weapon play is simply a way to explore imaginative worlds, test out social roles, and engage in playful storytelling. But for others—those who have experienced real violence—it can take on a much deeper significance. Children who have lived in homes or communities where violence, crime, or conflict is present may engage in weapon play differently. For these children, the themes of power, control, and survival are not just fantasy; they are part of their lived experience.

This raises an important question for early years practitioners: Is weapon play beneficial or harmful for these children? The answer is not straightforward—it depends entirely on the child, the context, and the way the play is structured and supported.

Weapon Play as a Tool for Processing Trauma

One of the most important functions of play is that it provides children with a safe space to make sense of their world. Research into trauma-informed practice shows that play can help children process difficult experiences by allowing them to replay events, experiment with alternative outcomes, and express emotions in a way that feels safe and manageable.

Children who have experienced violence may use weapon play to:

- Regain a sense of control – In real life, they may have felt powerless. In play, they can take on the role of the ‘protector’ or the ‘hero’, giving them a way to restore their sense of agency.

- Work through fears and anxieties – Play allows children to revisit scary experiences from a distance, making them feel more manageable.

- Express emotions safely – Rather than keeping feelings bottled up, children can act out anger, fear, and uncertainty in a pretend world where the stakes are lower.

However, we must be especially mindful of the distinction between power and violence. If a child’s play becomes repetitive, aggressive, or emotionally charged, it may be a sign that they are struggling to process real experiences rather than engaging in imaginative storytelling*. In these cases, practitioners should consider alternative ways to support emotional expression, such as small-world play, storytelling, or sensory activities.

*If you are concerned about any aspect of a child’s play, always seek advice from your Safeguarding lead

Supporting Children with Trauma in Weapon Play

To ensure weapon play remains beneficial rather than harmful, practitioners should:

✔ Provide safe, structured play environments – Designate spaces where role play can take place with clear guidelines and ‘safe’ props.

✔ Expand narratives beyond combat – Encourage children to explore alternative endings, like reconciliation or teamwork.

✔ Help children explore power in positive ways – Discuss what makes a character truly strong—bravery, intelligence, kindness—not just weapons.

How to Manage Weapon Play in Your Setting

Rather than banning weapon play outright, we should guide it. That means setting clear boundaries, facilitating positive interactions, and ensuring all children feel safe and included.

1. Set Clear Boundaries

Children need to know the rules of play. It’s not about saying, ‘No weapon play allowed.’ It’s about teaching children how to engage in it safely and respectfully.

Some key ground rules:

- Weapons must be imaginary or made from safe/risk-assessed materials.

- Play should involve cooperation, not domination (everyone should have a choice to join in or opt out).

- Children should understand the difference between fantasy and reality—we don’t ‘fight’ in real life.

2. Observe and Facilitate

Instead of standing on the sidelines waiting to intervene, practitioners should actively engage. Watch how children play. Are they negotiating roles? Are they cooperating? Is anyone getting upset? Step in when necessary—not to stop the play, but to redirect and guide it.

Ask open-ended questions like:

‘What’s your plan for the battle? How does that include everyone?’

‘How does your superhero help others?’

‘What happens after the battle? How do the characters solve problems without fighting?’

By engaging in their play, you help them think critically about their actions and encourage storytelling beyond ‘just fighting.’

3. Encourage Alternative Narratives

Weapon play doesn’t always have to be about battles. Give children opportunities to explore different storylines:

Rescue missions – Instead of fighting a villain, children might save a captured friend.

Problem-solving adventures – Can superheroes solve a mystery instead of using force?

Defence and protection – Knights can guard a castle and pirates can guard treasure rather than always attacking.

By helping children to broaden their narratives, we allow children to explore power and conflict in a way that encourages positive social interactions.

A Balanced Approach

Ultimately, weapon play isn’t something to be feared—it’s something that most children will engage in and so needs to be understood. Children will play with themes of power, conflict, and justice whether we allow it or not.

The best thing we can do is guide it, facilitate it, and use it as a learning tool.

- Weapon play does not cause aggression—it teaches self-regulation.

- Banning it doesn’t work—children will find a way to play it anyway.

- With the right support, it becomes a valuable learning experience.

- The most important lesson we can teach is that power is not the same as violence.

Booklist for Further Reading

For Practitioners

"Rethinking Superhero and Weapon Play" by Steven Popper

This book offers an insight into children's fascination with superheroes and weapon play, providing practical guidance for practitioners."Magic Capes, Amazing Powers: Transforming Superhero Play in the Classroom" by Eric Hoffman

This book takes an in-depth look at why children are so strongly attracted to superhero and weapons play, examining concerns from families and teachers, and suggesting practical solutions that consider the needs of both children and their adults."We Don't Play with Guns Here: War, Weapon and Superhero Play in the Early Years" by Penny Holland

This book explores the development and application of a zero-tolerance approach to war, weapon, and superhero play through the eyes of children and practitioners, challenging many taken-for-granted assumptions in early childhood education."Calling All Superheroes: Supporting and Developing Superhero Play in the Early Years" by Tamsin Grimmer

Tamsin examines superhero play and related themes, including death, weapons, rough-and-tumble play, and zero-tolerance policies, with lots of practical ideas."Rethinking Weapon Play in Early Childhood: How to Encourage Imagination, Kindness, and Consent in Your Classroom" by Lisa Broadie and Julie Marx

This book aims to inspire new ways of thinking about the kind of play ‘allowed’ in the classroom, and supporting the creation of supportive spaces for young children.

Enjoy this article?

Take a look at our post ‘I Hope That’s Not a Gun!’ where I explore this topic a little further:

References

Bryce-Clegg, A. (2014). Creative Role Play in the Early Years. Featherstone Education.

Holland, P. (2003). We Don’t Play with Guns Here: War, Weapon and Superhero Play in the Early Years. Open University Press.

Pellis, S., & Pellis, V. (2010). The Playful Brain: Venturing to the Limits of Neuroscience. Oneworld.

Garbarino, J. (2001). Lost Boys: Why Our Sons Turn Violent and How We Can Save Them. Free Press.

Goldstein, J. (2012). Play in Children’s Development, Health and Well-Being. Toy Industries of Europe.

Brown, S. (2010). Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. Penguin.

Lester, S., & Russell, W. (2018). Play for a Change: Play, Policy and Practice. National Children’s Bureau.

Wilson, E. O. (2013). The Social Conquest of Earth. Liveright Publishing.